You’re reading the web version of our email briefing on health policy, science and medical news. Sign up to get the next one.

Something different today.

This week, an almost year-long project came to fruition: The BMJ published my deep-dive on how COVID affects the immune system, after we recover.

I reviewed the literature, interviewed immunology experts worldwide, and cleared two rounds of peer review (and at least a few rounds of plain old editorial review).

The feature is quite science-heavy. So, here’s a plain-language brief on what it all means. Then, we’ll look at some news hits.

The neat split between “people with long COVID” and “everyone else” never did line up with clinical realities. A growing body of evidence suggests the after-effects of infection sit on a spectrum. They’re not the same for everyone, and for many of us they’re small.

Because truly never-infected people are now rare, most studies compare post-infection people with other post-infection people, so subtle but important changes are easy to miss.

In plain terms: for a while after recovering from COVID, our bodies aren’t as good at fending off other bugs. These changes are small, but across tens of millions of people, they add up.

This has been showing up in a few different ways over the past five years. More shingles, more bacterial infections in the weeks after a summer or winter wave, and more autoimmune disorders.

This doesn’t mean everyone is facing these harms. Nor that vaccines aren’t an important part of the solution. Vaccines likely blunt some of these risks. These ideas are also not new.

But there’s a sticky narrative that’s been floating around for a few years: that pandemic restrictions themselves are what led to the spiking infections we’ve seen since 2022. That might explain part of what we saw back when restrictions first lifted. It does not explain what’s happened since.

Each “respiratory season” brings its rash of headlines about unprecedented infection surges straining hospitals and making people unusually sick (RSV, group A strep, mycoplasma).

If “missed exposures” were the whole story, these effects would be briefer than they are, largest where restrictions lasted the longest, and concentrated in kids, who "missed out" on pathogen exposures for four or five months, back in 2020–2021.

Immunologists tell me that the average person’s immune system looks different than it did in 2019. That we’re walking around with more inflammation, and with immune systems that don’t work quite as well as they did in the beforetimes (on average).

So what can be done? Medical and policy leaders can be prudent and helpful, without any sense of drama or doom.

Improve indoor air. Keep vaccines and treatments easy to access for people who want and need them. Encourage testing and public alertness for secondary infections. Track post-infection complications with the same discipline we bring to acute care. Communicate scientific uncertainty honestly.

Many of us feel a little more tired than we used to. We go out less. We chalk it up to age, kids, and the economy. Maybe that is all it is. Maybe there is another contributor. We should be willing to find out.

Read more…

CBS’s 2022 partnership with Grifols aimed to fix domestic immunoglobulin (IG) shortages, with a pledge that Canadian plasma and products would stay in Canada.

Grifols now makes albumin for export in Montreal using IG “byproducts” from its U.S. plant, testing the spirit of its agreement.

Paying for blood donations is technically banned in BC, Ontario, and Quebec. But Ontario now allows Grifols to run paid clinics via a complex arrangement with Canadian Blood Services. Six Conservative MPs are pushing for a committee probe, though they may be most interested in Brookfield’s efforts to acquire Grifols last year, while Prime Minister Carney was still chair of the private equity firm.

Read more…

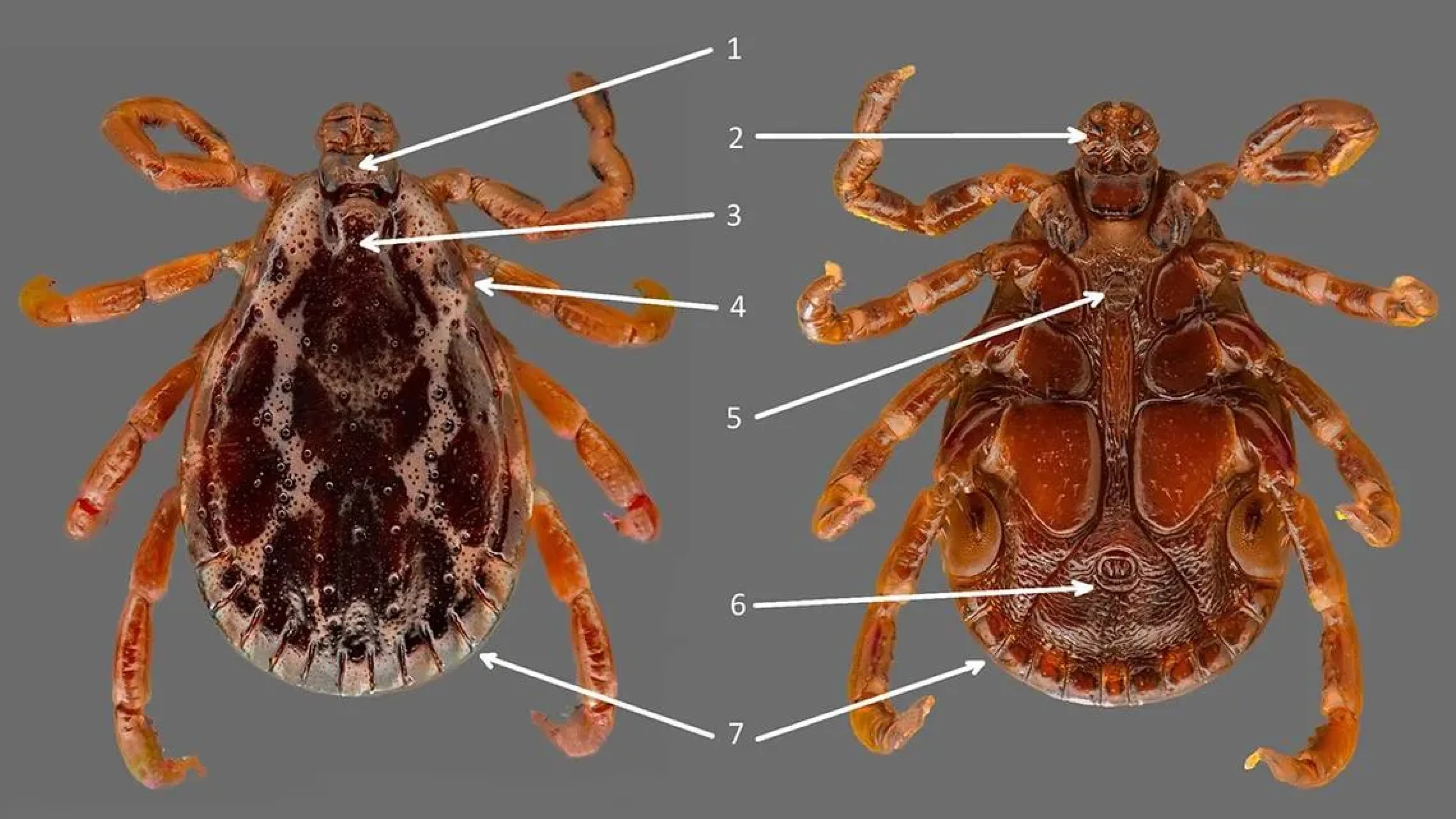

Quebec reported its first domestically-acquired RMSF case. RMSF is moving north as a result of climate disruption.

This isn’t Lyme. RMSF moves faster. Transmission occurs via the American dog tick, not the blacklegged tick that spreads Lyme. 5–10 per cent of cases are fatal, and early treatment saves lives. Because RMSF is historically rare in Canada, it — and dog ticks — aren’t well-tracked.

RMSF has also been circulating outside of Quebec. Ontario vets reported five dog cases this summer, including one fatal case. Prevention includes sensible stuff like wearing long sleeves and pants outdoors, using repellents, and doing tick checks.

Read more…

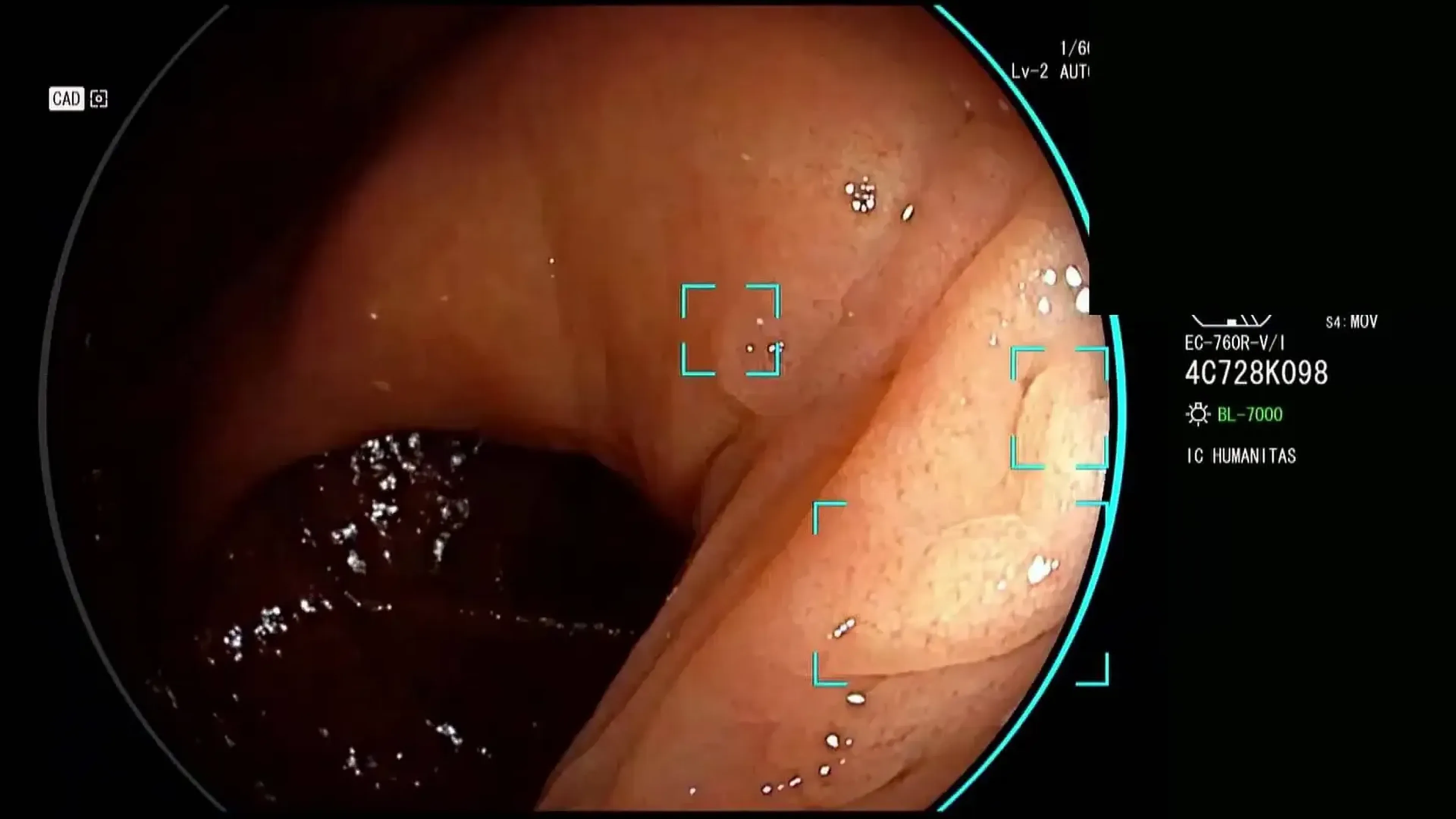

A Polish study found endoscopists who regularly used AI-assisted detection methods had a decreased ability to find adenomas when AI wasn’t in use.

Researchers found that adenoma-detection dropped 4% after routine AI use. Caveats: Observational study, short window. Not causal proof.

As clinical reliance on AI creeps in, baseline skills will slip. Hospitals could start tracking skill-indicators pre/post AI, and develop measures to help clinicians keep their skills sharp.

Read more…

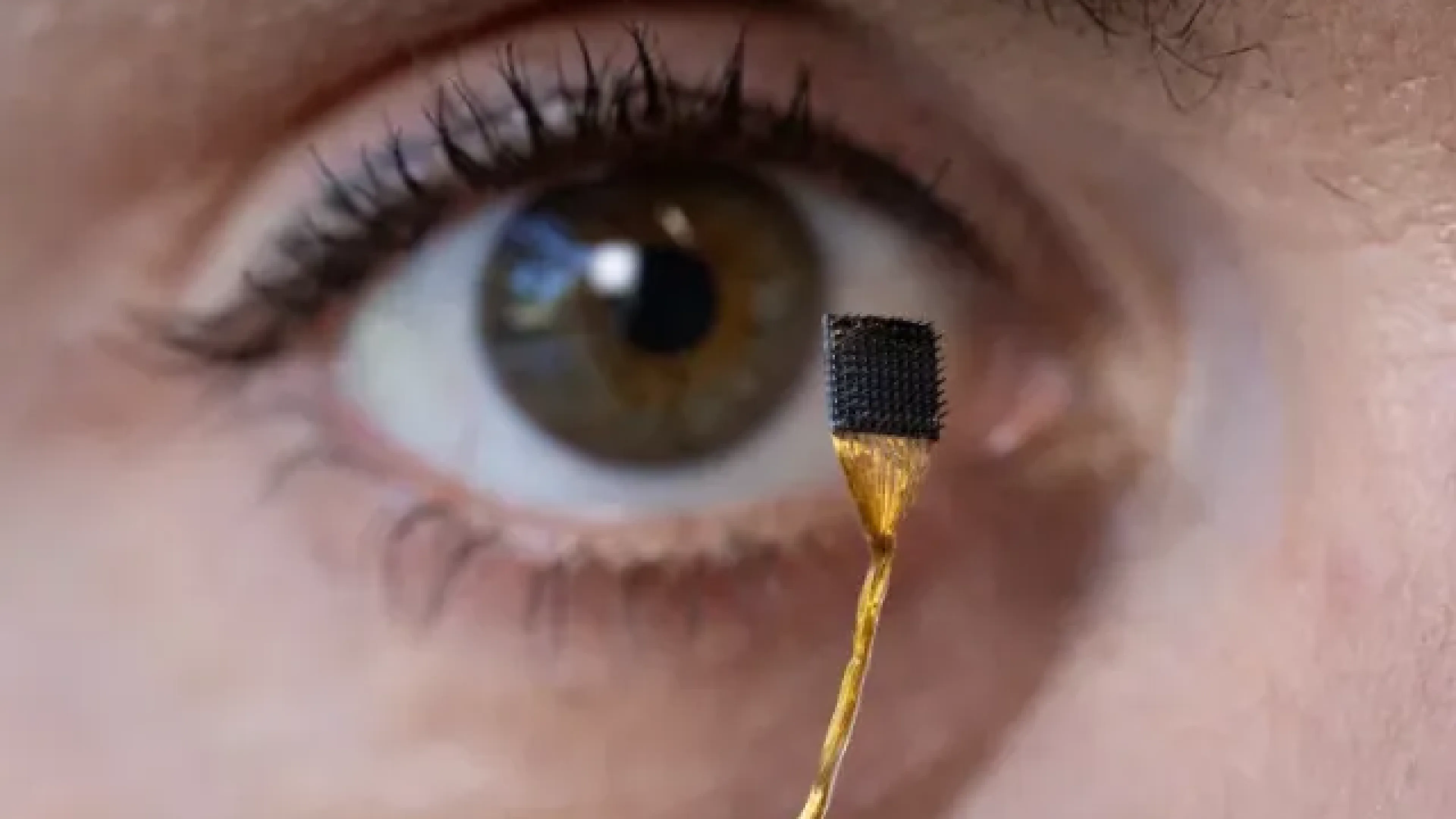

Implanted brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) that restore speech in paralysis also picked up “imagined” speech and decoded it with high accuracy.

In four BCI users, imagined speech produced brain signals that AI decoded into words with up to 74 percent accuracy from a 125,000 word vocabulary.

Researchers tested guardrails to prevent unintended leakage of participants’ thoughts. They first programmed the AI to ignore inner speech, which worked but slowed things down. They also tried using a wake phrase to permit decoding. With consumer BCIs on the way, standards for mental privacy and on-device controls are needed urgently.

Read more…

And that’s it for today.

Canada Healthwatch stays sharp because you are. Send questions, feedback, tips, or submissions our way. We read every note.

See you in a week, 👋

Nick Tsergas, Editor

Canada Healthwatch

[email protected] | canadahealthwatch.ca

Stay informed.

On the most important developments in Canadian health.

Get Canada’s essential briefing on health policy, science, and system change. Get Briefing