Canada is going all-in on AI, without the guardrails workers need

Nathan, a Toronto-based AI engineering manager for a Big Tech company, doesn’t take time off when he’s sick. Between coughing fits, he admits his work-life balance isn’t good. He asked that his surname not be used to avoid putting his job at risk.

Federal and provincial governments have committed multiple billions of dollars to anchor AI infrastructure in Canada, courting tech companies to expand domestic data centre capacity. But according to labour and policy experts, the AI gold rush is eclipsing scrutiny of how these systems will reshape work, and how they will test the limits of Canada’s labour protections.

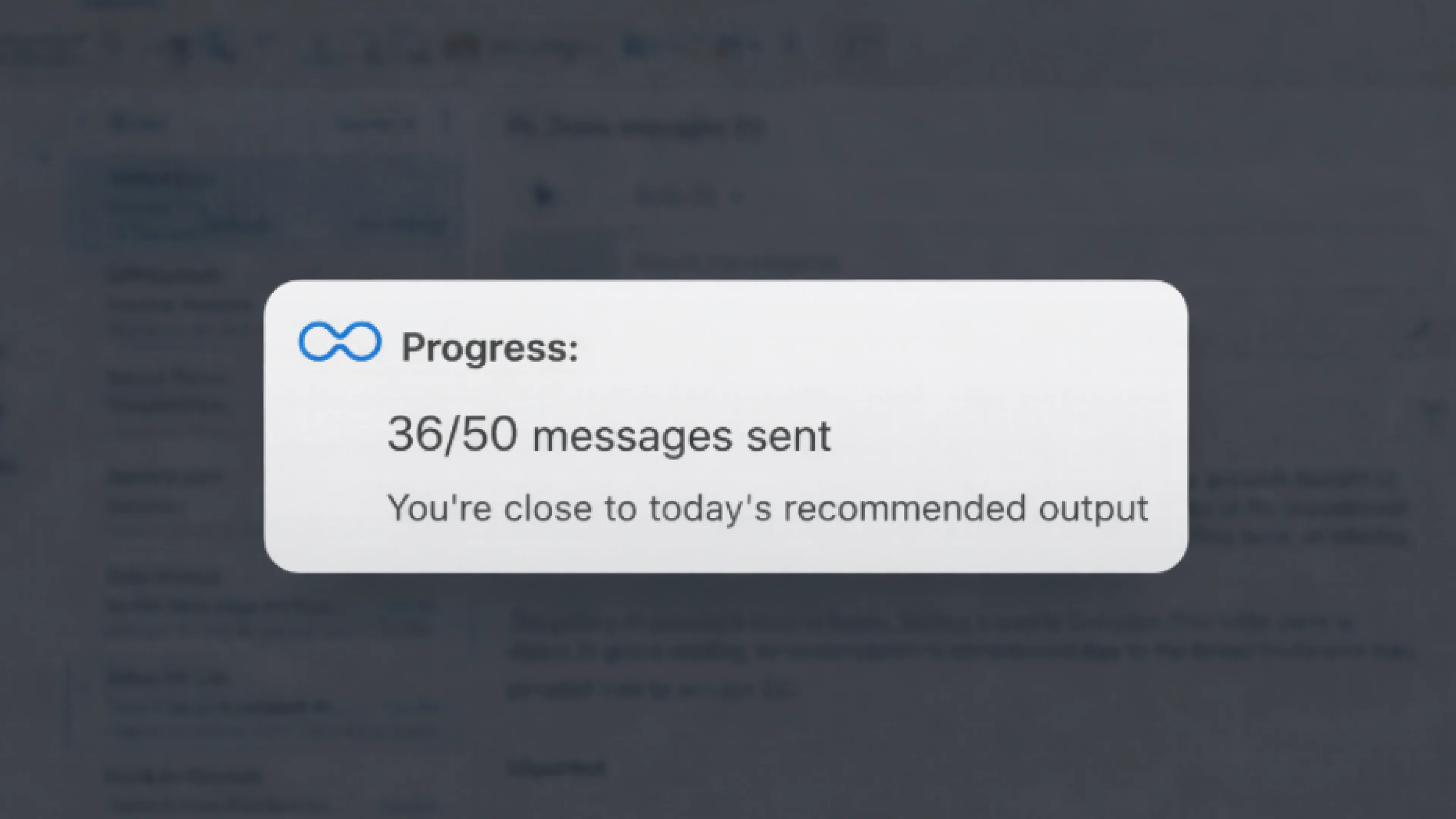

Nathan runs a 24/7 operation across time zones and is expected to respond to messages within minutes during his 12-hour shifts. He says the heightened pace has become normalized as AI infrastructure scales up.

But tech workers are not the only people negatively impacted by AI in the workplace. Kaylie Tiessen, Chief Economist at the SHIELD Institute, has been studying how AI algorithms risk the health and safety of people in non-tech jobs.

Potential job-loss is not the only side effect of mass AI adoption. “It’s not just about whether or not you lose your job,” Tiessen said. “There are so many mental health impacts we are not tracking.”

“More and more, workers are being directed by AI to work faster and be harder on their bodies,” Tiessen said. She also stressed the importance of task-diversity in making one’s work less physically and mentally taxing. “If an AI-enabled robot is bringing you boxes to stack and ship, that repetitive movement is harder on your body than going through the warehouse and doing different movements,” she said.

The same applies in the customer service world. Delegating easier and more enjoyable cases to AI chatbots means that by the time customers speak to a human, they are more frustrated. Tiessen said this is a recipe for misery and burnout.

Truck drivers must now contend with bully tactics from AI surveillance tools, also known as “bossware.” Cameras and sensors collect data on drivers’ eye movements, how hard they hit the brakes, and how fast they accelerate. When data deviates from algorithm-approved norms, it can be used to justify discipline or lost work. Tiessen said this makes drivers less confident and less safe on the road.

Office bossware, such as software to surveil computer mouse movements and keystrokes, became prevalent during the first years of the COVID pandemic when more people were working from home. In 2022, Ontario became the first province to require employers to notify employees of the nature of their monitoring practices.

“All of that data can potentially be used to discipline them later. That alone creates mental health strain and tremendous pressure,” Tiessen said. “It takes away their autonomy. Instead of making the decision that feels best to them, they’re making decisions based on what they think the algorithm is going to require.”

According to a recent study by METR, a non-profit that evaluates AI models, AI coding tools have been found to slow down coding work by 19 per cent. The finding undercuts claims that AI tools universally ease workloads, even as productivity expectations and investment continue to rise on this assumption.

Tiessen said AI companies should be required to make their systems transparent and to explain how algorithms function, and how they shape productivity expectations and decision-making inside workplaces.

“The Canadian government is more focused on facilitating the development and expansion of the commercial AI industry than on addressing the risks and anxieties that workers have,” said Chris Roberts, Director of Social and Economic Policy at the Canadian Labour Congress.

When people are being managed and having their wages determined by algorithms, Roberts said Canada needs proactive legislation, and that governments have been slow to put guardrails in place as AI systems evolve and spread.

Technological labour shocks occur when workers are de-skilled or lose partial or full employment. What is missing from the policy conversation, Roberts said, is any coordinated framework to prepare people for those shocks. “There’s virtually nothing."

Angelica Recierdo is a health writer, former tech worker, and trained nurse from the U.S.