Measles doesn’t care about your politics

Olivia Dahl died in 1962. Today, children are dying for the same reason: they weren’t vaccinated.

In 1986, Roald Dahl, the famous children’s author, wrote a letter to British parents, sharing the story of his eldest daughter, Olivia, who caught measles in 1962, when she was seven.

Dahl described how just when he thought she was getting better, suddenly, one morning, she wasn’t.

“‘Are you feeling all right?’ I asked her.

‘I feel all sleepy,’ she said.

In an hour, she was unconscious. In twelve hours she was dead.”

Olivia had developed a rare measles complication called encephalitis, or brain inflammation.

When it’s your child, “rare” becomes irrelevant.

A year later in 1963, the first measles vaccine was licensed — a measure that would likely have saved Olivia’s life.

When Roald Dahl shared Olivia’s story in 1986, Britain was seeing nearly 100,000 cases of measles a year, yet parents were choosing not to immunize their children.

Over the last fifty years, the World Health Organization estimates that essential vaccines have saved over 154 million lives globally, or “six lives a minute, every day, for five decades."

Sixty per cent of these lives saved are from measles vaccines.

Vaccination’s outsized effect on mortality comes from both preventing deaths from measles itself, and deaths related to the opportunistic infections that follow after the immune system is compromised.

By infecting long-lasting memory cells, the measles virus causes immune amnesia for two to three years, wiping out up to 70 per cent of a person’s antibodies to other pathogens — decimating immunity built through past infections and vaccines.

As one person wrote:

“Measles destroyed my health — my parents didn’t vaccinate me.”

“I got every single illness going for the next five years or so. I was ill for almost the entirety of my first year at uni with coughs, colds, tonsillitis, chest infections, ear and kidney infections.

I had no defense against anything."

At the population level, failing to contain measles outbreaks will open the door to many more infectious diseases, as the recently infected will now join the ranks of the vulnerable.

* * *

What Roald Dahl described in 1986 is vaccine hesitancy, which we define as a delay in acceptance, or a refusal of vaccines despite their availability.

The ongoing COVID pandemic worsened vaccine hesitancy, through an unrelenting torrent of misinformation and disinformation on social media. Public distrust in scientific and medical authorities has translated into a broader reluctance to accept vaccines across the board — even those that have been in-use for decades.

Vaccine hesitancy is in the news again with the global resurgence of measles, including an epidemic in Ontario with more than 1,400 cases and another in Texas and multiple neighbouring states.

Sadly, an adult in New Mexico and two Texas children have died. Last year, a child died in Ontario. All were unvaccinated.

Alberta is also in the midst of a measles outbreak. As of now, there are 326 cases, mainly in children and teens. Nearly all cases are in those who are un- or under-immunized.

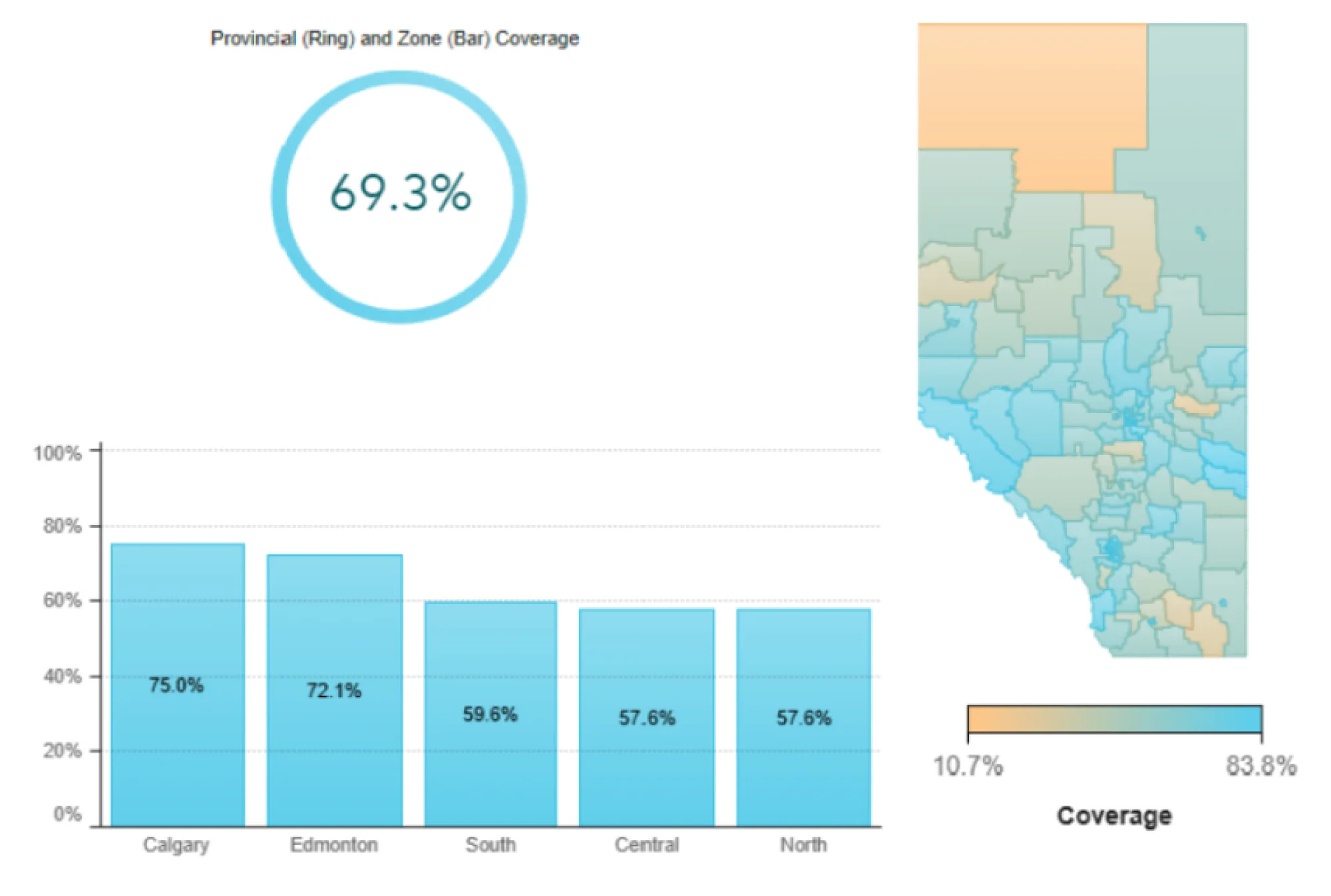

As far back as 2023, Alberta’s measles immunization rates were as low as 10–30 per cent in some rural areas.

Measles vaccine coverage by health zone in Alberta, 2023 (provincial data: “two doses by age two”).

These numbers are frightening. Like dry kindling waiting for a spark, these communities are highly vulnerable to a fast-moving measles outbreak. Such an outbreak will be a predictable — and preventable — tragedy.

In 1998, Canada eliminated measles through vaccination, surveillance and a community immunity rate above 95 per cent. For this reason, many today have never seen measles. It’s easy to underestimate its impact.

Measles is the most contagious disease we know of.

One infected person can infect 12–18 others (for the Omicron COVID variant, that number was 7). Each infected person can then infect 12–18 others, seeding an explosive, exponential chain of infection.

Measles, like SARS-CoV-2 spreads through tiny infectious aerosols that linger in the air we breathe, even after the infected source has left the room. In a classroom with poor ventilation and air filtration, one infectious student can infect up to 90 per cent of their susceptible classmates. Frustratingly, parents’ pleas for clean air in schools and childcare settings have been stonewalled.

Because it is so wildly contagious, eliminating measles requires such a high vaccination rate. High community immunity (of at least 95 per cent) is needed to protect the roughly two million Canadians who cannot be immunized — babies younger than 6 months, and people who are pregnant or otherwise immuno-compromised.

This is why an “Every-person-for-themselves” approach to measles vaccination is incompatible with Public Health’s role. But Public Health is taking a laissez-faire approach at this critical juncture, enabling and surrendering to vaccine hesitancy at a time when the cost could be devastating.

An outbreak in New Brunswick stemming from a Mennonite wedding last fall seeded the outbreak in Ontario, which in turn seeded what appears to be an early epidemic in Alberta. Mexico has just put out a measles travel advisory for Canada, and ironically, so did New York State. We should take that as a vote of no confidence in our public health.

For months, both Ontario and Alberta should have been pulling out all the stops to urgently contain small, localized outbreaks. With exponential growth and low vaccination rates, delayed and tepid outbreak response can lead to cascading crises, making public health’s task more difficult, and more expensive, and more tragic.

Yet, there has been little sense of urgency amongst our leaders. In Alberta, it took the abrupt resignation of the chief medical officer and his scathing op-ed along with three children in the ICU for the health minister to finally announce a province-wide immunization campaign.

Recent modelling shows what a return of endemic measles would look like in the U.S. Even a small decline in vaccine uptake would lead to more than 11 million measles cases and tens of thousands of preventable deaths (directly attributable to measles) over the next 25 years.

Endemic measles is a nightmare scenario — even without accounting for immune amnesia. With measles, there can be no complacency.

Back in 1986, Roald Dahl ended his letter to British parents thus:

“I know how happy she [his 7 year old daughter, Olivia] would be if only she could know that her death had helped to save a good deal of illness and death among other children.”

No parent should have to bury their child because of measles.

---

Dr. Lyne Filiatrault is a retired emergency physician. On March 7 2003, her ED team quickly isolated Vancouver’s first SARS patient, shielding Vancouver from a major SARS outbreak. A past member of Protect Our Province B.C., she is now part of the Canadian Aerosol Transmission Coalition.

Dr. Arijit Chakravarty is the CEO of Fractal Therapeutics, which focuses on applying mathematical modeling to drug discovery and development. Over the past five years, he has led an interdisciplinary team of volunteers in publishing over twenty peer-reviewed papers on SARS-CoV-2, including several focused on in-school COVID transmission.

A different version of this article was first published in the Surrey Now-Leader.