Trump’s cronies aren’t what broke public health

The structural blind spots that undermine medical progress and how to fix them.

Public health didn’t die when RFK Jr. became Trump’s Health Secretary. It was already on life support, hamstrung by a siege mentality, turf wars, and an erosion of its connection to science.

Recently, the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care had its activities paused by the federal government after it recommended that breast cancer screening not be offered to women aged 40–49, despite sharply rising cancer rates in this age group.

The controversy raised a deeper question: how exactly is medical guidance made — and why does it so often resist change, even in the face of compelling evidence?

Problems with the Task Force are well-documented. But they aren’t unique, and they aren’t new.

In 1846, maternal deaths at the Vienna General Hospital were dramatically higher in the doctors’ ward than the midwives’ ward. The difference was staggering: 11.4 per cent of patients seen by doctors died, compared to just 2.7 per cent of those seen by midwives.

Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis noticed that doctors were going directly from autopsies to deliveries without washing their hands. He introduced a handwashing protocol. The next year, mortality fell to just 1.27 per cent.

The evidence was clear. But Semmelweis was ridiculed and rejected by the medical establishment of his time. His career, and then his mental health, suffered greatly.

In 1865, he was committed to an asylum. He was beaten to death by attendants while trying to escape.

His story isn’t a metaphor. It’s a mirror. Ignoring inconvenient scientific truths is a longstanding, dangerous pattern.

So, why is medicine still like this?

The answer lies in structural flaws in medical decision-making.

The most spectacular failure in recent memory was the refusal of international health leaders to address the cold, hard, scientific reality of airborne COVID transmission.

In the words of the WHO’s current Chief Scientist, it was a “very big mistake,” which cost “an enormous number of lives.” So, why did they get it so wrong (and how do we stop them from doing it again)?

Five years ago, on April 3, 2020, the world’s top bioaerosol scientists warned the WHO that COVID was transmitted in infectious aerosols, tiny particles that drift in the air like smoke. They were right. And they were shouted down.

The WHO’s guidance for managing the novel pathogen, SARS-CoV-2, rejected the latest science along with lessons learned from mistakes made twenty years earlier with SARS-CoV-1. In an instant, decades of evidence were brushed aside.

The refusal to “follow the science” on airborne transmission may well be one of the deadliest mistakes ever made.

It wasted our best chance to stop the pandemic before it got started. Excess deaths are already estimated to exceed 25 million, and are still climbing. Millions of years of human life and something in the ballpark of a trillion dollars per year are still being lost to long COVID — in the OECD alone.

This exemplifies a recurring pattern of similar institutional failures, in which medical decision-making rejects outside expertise, replacing it with opaque processes biased towards inaction, that often seem strangely consistent with the personal opinions of those involved.

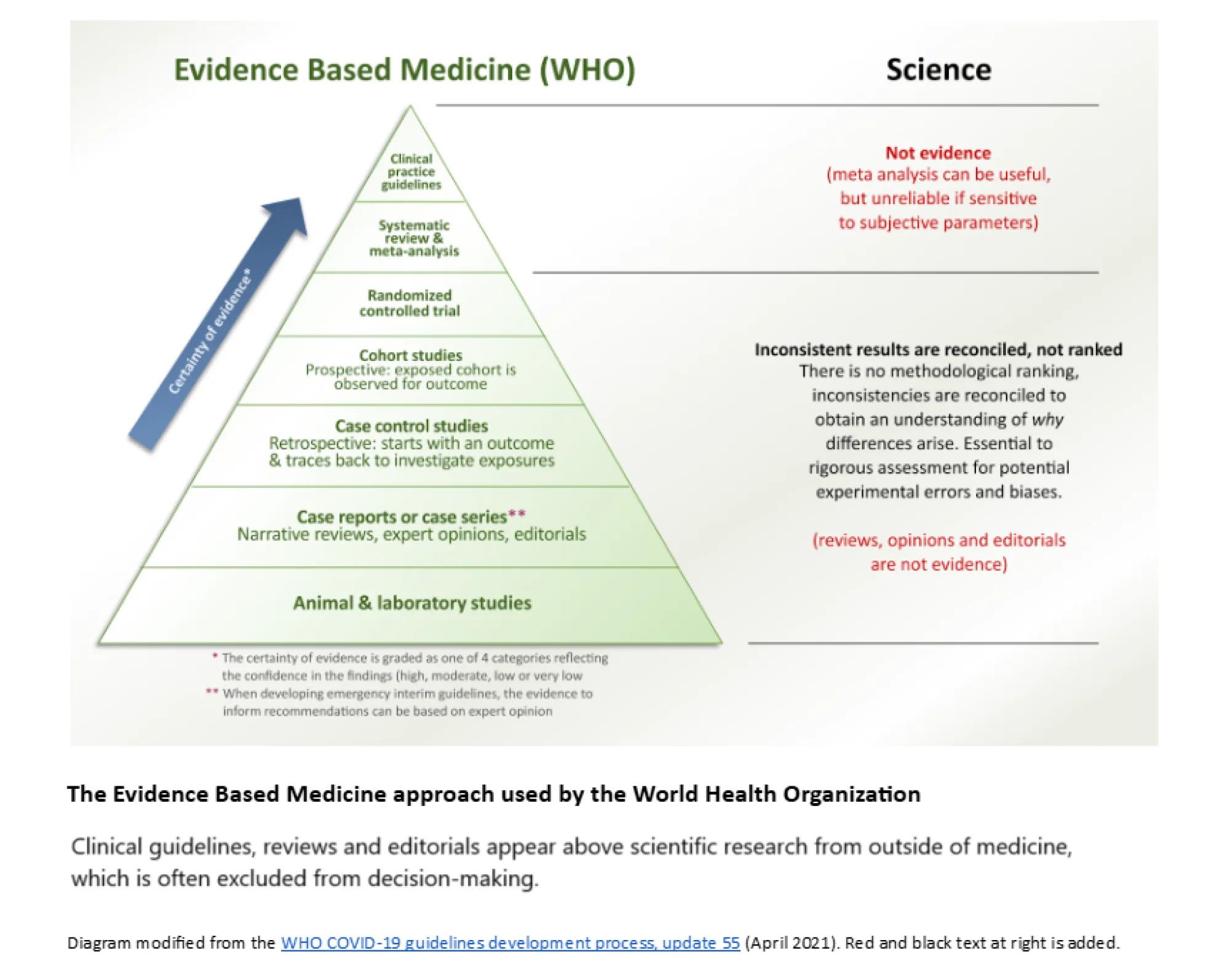

Just like the Task Force, the WHO relies on a simplistic framework called Evidence Based Medicine (EBM), a system designed to help front-line clinicians make quick decisions when they don’t have the time or expertise for a deep dive into the science.

It’s a legitimate approach under the right circumstances, but it’s not rigorous science.

Somewhere along the way, that distinction got lost. What began as a practical tool for non-experts was rebranded as definitive science. EBM’s dogmatic authorities claimed the right to override both science and clinical expertise, cherry-picking which evidence counts and which gets discarded.

In its increasingly rigid hierarchy, secondary sources are elevated above primary data. That’s a huge red flag akin to watching only a movie trailer and pretending you’ve seen the film. Clinical trials land somewhere in the middle. And everything else — science, engineering, occupational health and safety — is shoved to the bottom, beneath even the editorials of EBM’s true believers.

Evidence can be down-ranked (or occasionally up-ranked) by a level or two based on evaluators’ subjective judgments, through processes such as GRADE — “Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations.”

While often marketed to policymakers and the public as a rigorous scientific approach, even EBM adherents recognize GRADE is unavoidably prone to bias. Different evaluators produce different results.

The outcomes depend on who is selected to participate — and how much expertise they bring to the table. Different pickers, different cherries.

Despite being tasked with evaluating science, these groups often actively exclude scientists. Their leaders frequently lack PhD- or even MSc-level scientific training outside the EBM echo chamber.

And an MD is not a PhD. Not better, not worse. Just different.

This is important, because any research can contain errors that require deep expertise to identify, and the clinical trials EBM practitioners hold up as their “gold standard” are no exception. There simply are no shortcuts to scientific expertise. You can’t find errors you don’t understand.

Without a rigorous scientific foundation, a clinician assessing biomedical research is like a molecular biologist observing brain surgery. No matter how good they are at the job they trained for, the fact that they don’t see a problem doesn’t mean there isn’t one.

EBM often functions as a closed loop, producing studies of variable quality, marking its own homework, and rolling the results straight into guidance. Problems go unnoticed.

Basic mistakes accumulate. Inconsistent data get averaged into statistical noise. And no intervention — be it masking or breast cancer screening — ends up looking like it works.

The result is a celebration of do-nothing medicine: smug commentary on “overdiagnosis” and “overtreatment,” that never stops to consider whether the failure lies in the intervention — or the analysis.

It’s easy to see how institutional medical cultures become trapped in tar-pits of groupthink, as we’ve seen with COVID, incapable of admitting, or even recognizing, their own mistakes.

Medical chauvinism has left public health leaders decades out of date on critical topics, and getting it right often seems to matter less than avoiding the admission that they got it wrong the first time.

The public is right to ask why glaring, deadly failures in public health communication still haven’t been addressed.

EBM’s own methods for detecting bias are themselves vulnerable — to bias, to conflicts of interest, and to the Dunning-Kruger effect. That becomes dangerous when practitioners are assessing research tied to their own past decisions. The reputational stakes are obvious.

In the U.S., fringe ideologues now hold the reins of key health science institutions. And the subjectivity at the core of EBM makes it alarmingly easy to manipulate.

The same system that once laundered the opinions of establishment authorities can also be weaponized to legitimize pseudoscience. Junk research will be cherry-picked, then mass-produced, to rewrite medicine, distort science and revise history.

Some of the same actors who failed so catastrophically at the outset of the pandemic may join in the fun, hoping to rewrite their own roles.

Watch closely. There will be attempts to normalize a new Lysenkoism — to declare that vaccines are dangerous, long COVID isn’t real, respirators don’t work, and that “lockdowns” (many shorter than summer vacation) caused rising illness in children who weren’t even born at the time.

The medical profession has an obligation to speak out publicly.

A few courageous clinicians have already joined transdisciplinary teams pushing back against misinformation spread by official sources. But too many have stayed quiet. And silence, in the face of failure, is complicity.

Too often, those who do speak up are unsupported by their colleagues, and pay a significant personal price. We’re living out the ethics essay you wrote for your med school application. Did you mean it?

With measles staging a comeback, H5N1 a looming threat and COVID out of control, we urgently need to restore trust in our public health institutions.

That starts with transparency, humility, and a respect for other disciplines that has been so strikingly absent throughout the pandemic. It also means walking away from a toxic orthodoxy that stretches back in time through the turf wars of SARS, to Semmelweis and beyond.

The public has a right to trustworthy medical guidance for everything from COVID to cancer screening. It should be built on a foundation of rigorous science and diverse expertise — not simplistic shortcuts, political games, and opinion-laundering.

The suspension of the Task Force is a good start, but we still have a long way to go.

---

Mark Ungrin is an Associate Professor at the University of Calgary and a translational interdisciplinary researcher funded by all three of Canada’s Tri-Agencies, whose technologies are used globally and on the International Space Station.