It's Canada’s ‘brain gain’ moment — if we don’t flub it

“We don’t want to miss this window,” says Dr. Joss Reimer, president of the Canadian Medical Association.

She says in the face of the chaos unfolding to the south, it would be a "small silver lining to have Canada gain a tremendous amount of medical and scientific expertise."

Over the past six months, the Medical Council of Canada has seen a twelve-fold increase in U.S. doctors initiating the licensing process. Nova Scotia is already onboarding its first cohort. Saskatchewan is advertising directly to American physicians, and Manitoba is preparing its own campaign.

Canada, it seems, has a historic opportunity. The question is: will Ottawa take it?

“The immigration system is not fast, and it’s not efficient,” says Alex Munter, the CMA’s newly appointed CEO and former head of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario.

Munter says when he was at CHEO, it wasn’t unusual for it to take years to bring a physician into the country.

One physician who recently made the move from the U.S. to Canada had much to say about the roadblocks he faced in the resettlement process.

He spoke anonymously, fearing reprisal from figures in the U.S. Canada Healthwatch has verified his identity.

He says the U.S. government could make it "very difficult" for physicians to leave for Canada, should the mood strike. And he wonders if the opportunity to recruit them at scale may be time-limited.

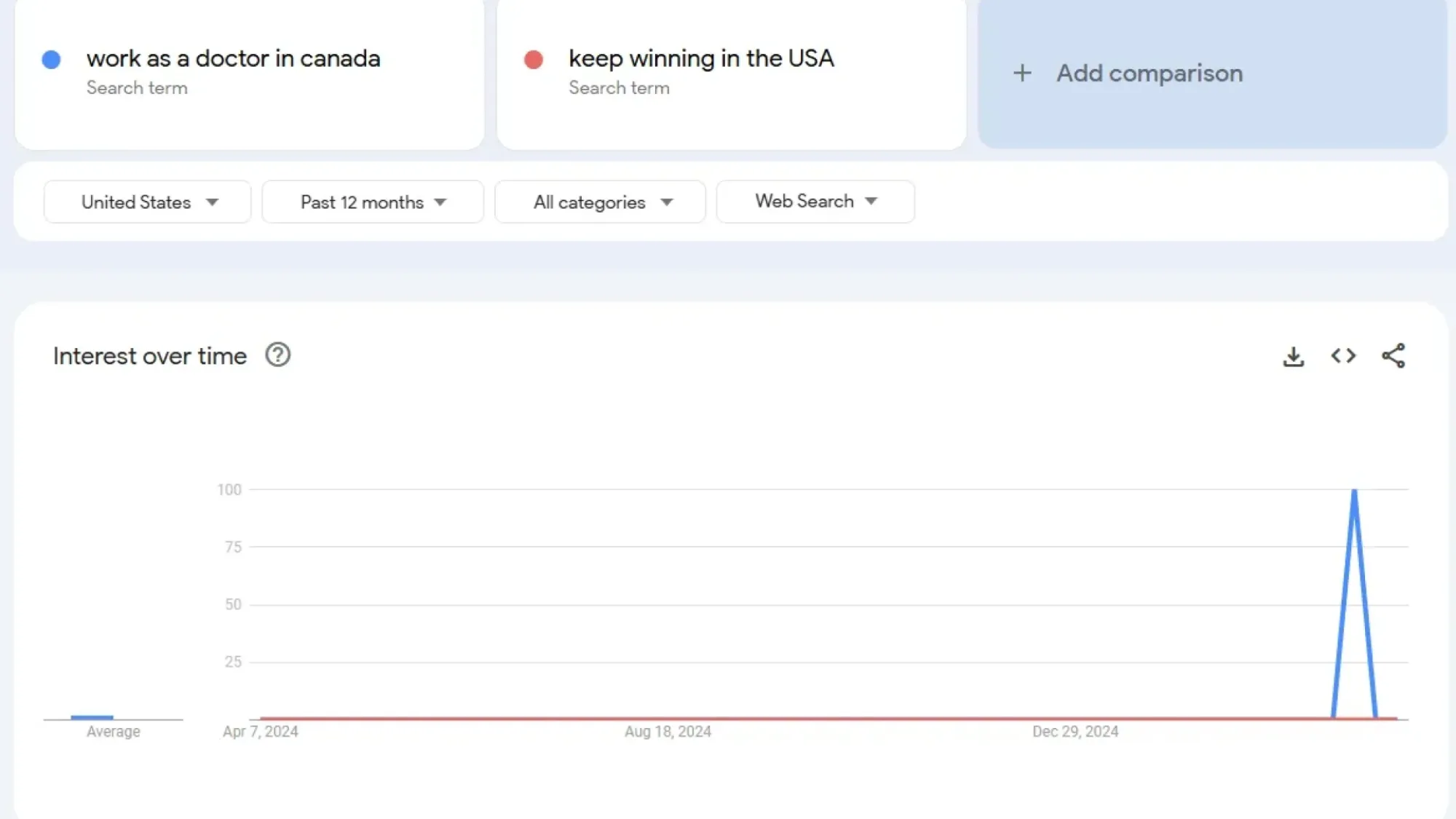

Google search interest in “work as a doctor in Canada” spiked last month, as disillusionment spreads south of the border.

He began the immigration process immediately after last year’s U.S. presidential election. After “a lot of fees” and time spent "filling out forms and making tons of phone calls,” he began working in a B.C. emergency room — five months later.

He says representatives from the Medical Council of Canada, provincial colleges, hospital associations, and government ministries (among others) “need to work together in a single office,” to drastically reduce the paperwork and administrative burden involved in making the move.

“This would be probably the only thing that would facilitate [B.C. Health Minister Josie] Osborne’s goal of licensure in six weeks,” he says.

“To get a SIN you need a bank account. But even after I got one I couldn’t get my SIN.

I handled it. But it was just dumb.”

This bureaucratic gauntlet is exactly what the CMA is hoping to eliminate. Munter says Ottawa already has the tools it needs.

“The Minister of Immigration has the authority to create special pathways,” he says, pointing to efforts to expedite immigration for Ukrainians, and previously, Afghans.

“We need the federal government to be helping from the immigration side,” Reimer says. “Health Canada’s own report said we’re 23,000 family physicians short.”

Munter also points to the federal requirement for Labour Market Impact Assessments — a lengthy step in which hospitals must demonstrate that they tried to hire within Canada first.

Munter, Reimer, and the CMA are calling for two specific federal actions:

- A dedicated immigration pathway to accommodate physicians fleeing the U.S.

- An exemption on Labour Market Impact Assessments for physician jobs

Munter says two ministries — Immigration, and Jobs and Families (formerly Labour) — will both be needed to achieve these objectives. Until then, he says, things at the federal level are too cumbersome to fully realize the brain gain.