How denial of airborne COVID transmission broke the world

As we mark five years since the emergence of SARS-COV-2, the most grievous error of the global pandemic response has become very clear.

It’s not “lockdowns,” as many right-leaning folks might suggest. Nor is it the inflation-stoking government support measures and central bank policies that many have argued were highly excessive. It’s not even the failure to address online health misinformation, as centrists and leftists might claim. It’s even more basic and essential than that.

Indeed, these concerns were partly induced by a single major scientific inaccuracy first illustrated at the World Health Organization (WHO) Coronavirus press conference on Feb. 11, 2020, when WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said:

Failure to reasonably presume, then later accept the airborne spread of COVID and operationalize the appropriate structural mitigations is at the source of every major shortcoming in our response to the pandemic, and every major form of physical, mental, economic and social harm it has brought about. It doomed our public health, social and economic responses, ensuring they would not be fully effective, appropriately targeted and minimally disruptive, ultimately leading to many divisions in society we see today.

Allow me to explain. Let’s imagine a world where key experts and evidence were not discounted, and where the dominance of airborne transmission of SARS-COV-2 was quickly accepted and acted upon.

Before we get to that, it’s important to understand that the focus on “droplet transmission” has always been an inaccurate and dogmatic representation of the physics of SARS-COV-2, which mostly spreads in small aerosols that people release during simple behaviours like breathing and talking, and that remain suspended in the air like smoke. SARS1 was also famously airborne. Many of the world’s leading bioaerosol scientists quickly recognized the clear evidence of airborne COVID transmission but were dismissed and excluded from policymaking input by gatekeepers at every level. In October 2022, Jeremy Farrar – who months later became Chief Scientist of the WHO – said it “was a very big mistake” to not take aerosol transmission seriously, and that airborne mitigations “would have saved an enormous number of lives.”

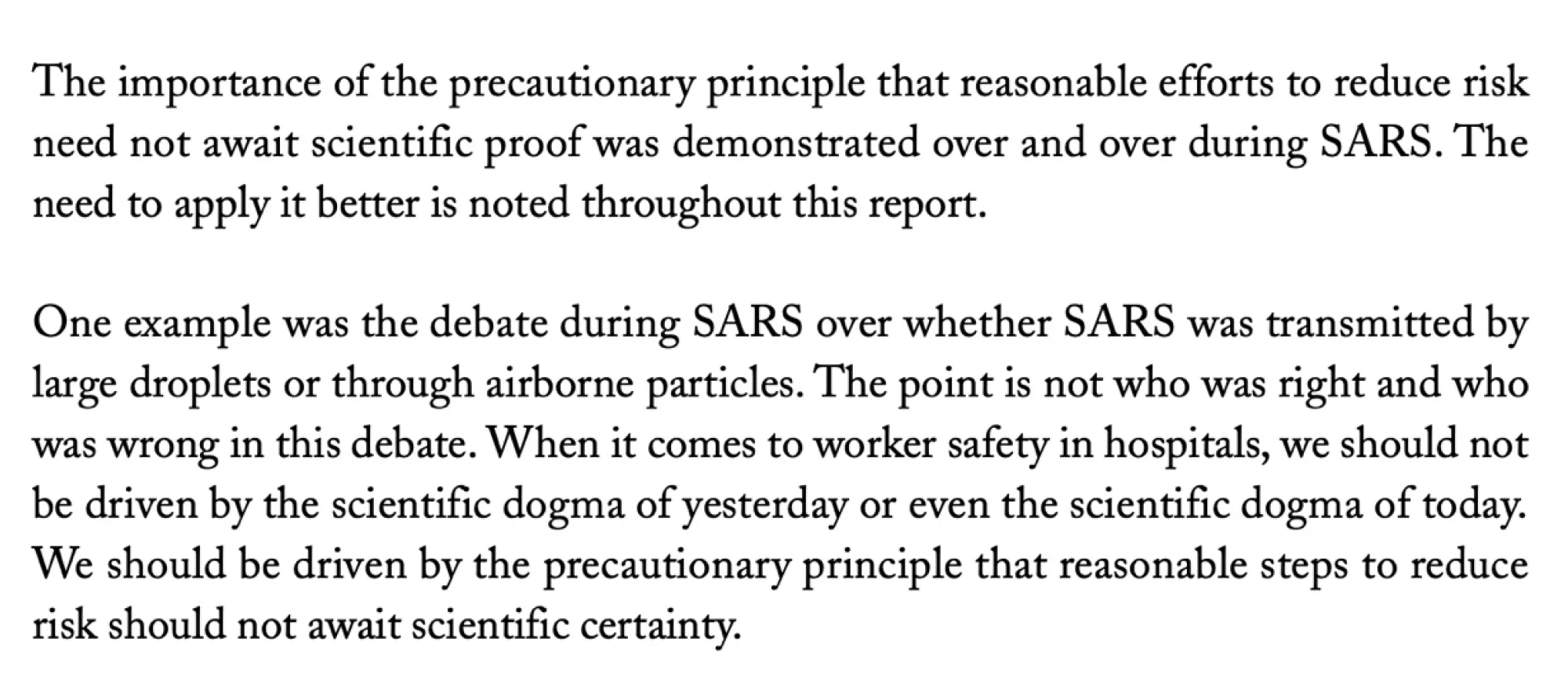

Figure 1.-SARS1 Commission Final Report, Ontario, Canada, 2006

A second important fact is that N95 respirators are specifically designed to protect from aerosols. By comparison, surgical masks have large air gaps and are not designed to protect from aerosols. Respirators are so effective that United Kingdom research has indicated their use by the public would have dropped the rate of COVID transmission by an estimated factor of 9, compared with 0.6 for surgical masks. A factor of 9 is enough to put SARS-COV-2 into exponential decay, meaning the virus would have been highly suppressed for as long as respirator use continued. The exponential math of viral spread also means that perfect masking compliance would not have been required to achieve suppression.

Let’s consider a timeline in which these facts had been acted upon.

Lockdowns

With airborne mitigations, many of the common complaints about “lockdowns” would never have materialized. Most closures would have remained necessary for a briefer period, until respirator manufacturing ramped up and respirators were distributed to the public for use in shared spaces.

Simultaneously, a fraction of the trillions saved by reducing the length of economic closures would have been spent to begin installing greatly improved ventilation, filtration and germicidal lighting systems (which can generate dozens of air change equivalents per hour) in every public indoor space, starting with schools, hospitals and other congregate settings. Public reporting of indoor air data like CO2 levels would have been mandated, along with the deployment of air quality inspectors analogous to those used to audit commercial kitchens. These are the structural mitigations that greatly reduce public health reliance on behavioural compliance, i.e. masking.

School closures would have been uniformly short-lived, minimally disrupting children’s learning and their parents’ work, and ending once respirator masks could be provided and used. Contemporaneous overhauls of indoor air quality systems would have greatly reduced transmission of COVID and other viruses while improving student health, attendance and academic performance. Some anti-mask sentiment would have developed over time, but by the time it could become an overpowering force, air quality improvements would largely have been completed and optional masking would have been feasible with low transmission.

Figure 2-New engineering standards for preventing airborne infections indoors have been publicly available for almost two years.

Health care

In hospitals, staff would have received N95 respirators within the first months and used them continuously, and air quality improvements would have been implemented. Staff would have ceased using surgical masks. Millions of health-care workers worldwide would have been spared infections, Long COVID or death, increasing the available experienced workforce and reducing rates of burnout-related resignation.

Millions of patient hospitalizations and deaths would have been prevented by societal mitigations; millions of hospital-acquired COVID infections would never have happened – averting the ongoing health-care overcapacity and collapse we continue to experience today. Hundreds of billions to trillions in health-care costs could have been saved globally.

Antivaccine sentiment

While existing COVID-19 vaccines prevent hospitalization, death and some Long COVID, their inability to durably prevent infection with the efficacy initially advertised by key officials likely contributed to decreased uptake of updated formulations. Some people misunderstood the value of vaccination and questioned the value of periodic boosters after still being infected despite vaccination.

Airborne mitigations would have greatly reduced viral transmission and therefore reduced evolution, that is to say the production of new variants. Consequently, this would have increased the average efficacy of vaccines by enabling periodically updated formulations to more closely match currently circulating variants instead of being far behind. The increased effectiveness of vaccines and the decreased rates of infection would have thwarted much of the public’s learned apathy, very likely improving ongoing vaccine uptake.

Superior vaccine effectiveness and greatly reduced transmission also would have helped neutralize the narratives of vaccine skeptics. The huge reduction in COVID-induced thromboses, organ damage and new chronic medical conditions like Long COVID (estimated to have impacted 400 million people) would have prevented many individuals from blaming vaccine injury for their viral ills, reducing the growth of antivaccination attitudes and the likelihood of politicians strategically weaponizing this subculture to sow division and seek power as we see today.

Anti-mask sentiment

Millions of people have been infected while wearing cloth and surgical masks. This has contributed to a commonly held belief that masks don’t work, even though respirators are highly effective. The early use of appropriate airborne personal protective equipment in the form of respirators would have reduced the popularity of the myth that “masks don’t work.”

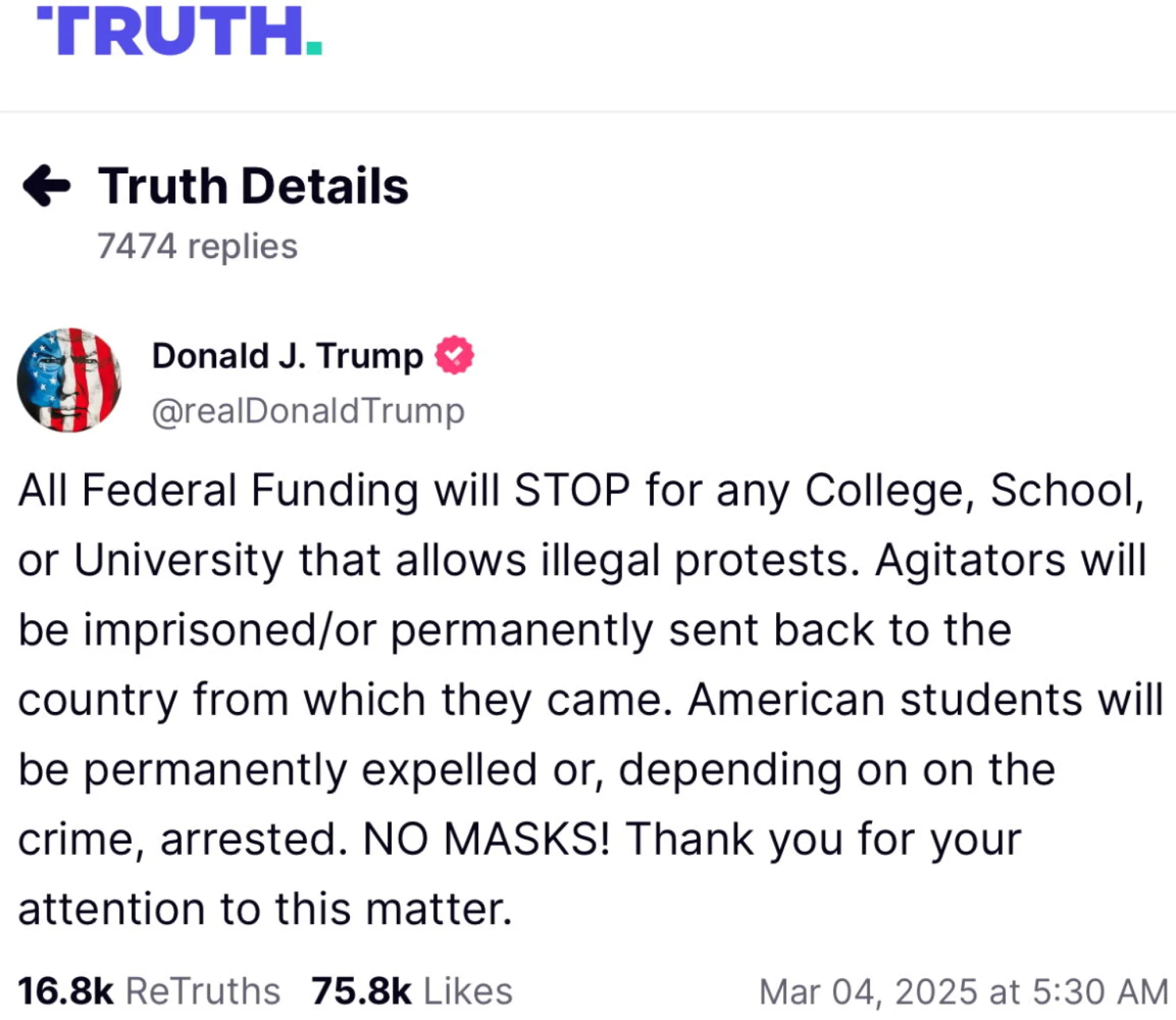

Today, the politicization of masking has led to disinformation campaigns and newly spreading mask bans that threaten not only people’s health but also their civil liberties.

Figure 3-President Trump proclaiming “NO MASKS!” and threatening colleges over political protests.

Economic harm

As you’ve likely gathered by now, operationalizing a proper response with respirator masking and indoor air improvements would have allowed the economy to operate mostly normally, with a few exceptions. Airborne mitigations would have been appropriately targeted and minimally disruptive. As such, global government debt spending to fund citizen and business supports could have been reduced by trillions of dollars; what was spent could have been targeted to workers and industries experiencing more significant impacts, such as the restaurant sector. This would have prevented most profiteering, unnecessary corporate subsidizing and the hollowing out of small businesses in favour of large corporations, all of which occurred due to inequitably applied government programs.

The massive reduction in economic shock inherent in an airborne mitigation strategy would have altered central banks’ pandemic policies on a global scale and prevented much of the inflation crisis. Interest rates would still have dropped as the pandemic spread, but likely with far less accompanying quantitative easing, and with a quicker return to more historical neutral rates and policies. The ability for logistical supply chains to operate with far fewer serious disruptions would likewise have averted much of the observed increases in input and manufacturing costs, further reducing inflationary pressures.

The newly generated multi-billion- and trillion-dollar sovereign debts currently affecting sociopolitical and economic stability worldwide would have been greatly reduced. The “K-shaped” economic recovery whereby wealth stratification between the wealthy and poor/middle class skyrocketed would be less severe. Lower inflation and government debt could have prevented millions from falling below the poverty line.

Social disunity and polarization

Social disunity and polarization today is multifactorial, but partly stems from several key changes affecting people and their environment – namely increased poverty, erosion of purchasing power, unprocessed trauma and grief, worsening physical and mental health, and the top-down promotion of directives like “you do you” – the antisocial idea implying people have a right to recklessly infect and harm others in the pursuit of self-interest.

Airborne mitigation would have prevented a significant amount of disunity and polarization – even if we set aside the reality of COVID-induced brain damage, the strong association between infection and new onset mental health disorders, and hypotheses about potential impacts on personality. Far fewer individuals would be grief stricken by loss or chronic illness; fewer might have turned to denialism, conspiracies or anti-scientific explanations to assuage themselves. Depression from social isolation would have been reduced. Relatively better purchasing power would have decreased persistent stress over obtaining the basic necessities of life, widespread feelings of helplessness about corporate servitude and, consequentially, apathy and antisocial behaviour. Politicization of disagreement as well as hatemongering by politicians and bad actors may have been reduced with less fertile ground to sow the seeds of disunity. As a result, subsequent leaders may not have adopted such deeply anti-science perspectives, and we might not be on the precarious political path we face today.

A world fractured

Unfortunately, due in large part to the failure to identify and ongoing failure to act on the basic problem the pandemic presented – airborne COVID transmission – we live in a fragmented world. The problems stemming from this failure continue to compound across all aspects of life.

Instead of truly fixing the core problem, one day, we were told by corporations and politicians that the pandemic was over. We decided to agree. Pretending that the problem was solved felt easy, and unprocessed grief about the loss of the pre-COVID era continues to reinforce this frame of thought.

Indeed, the CDC for years has focused on telling people to wash their hands to prevent the spread of COVID, despite the fact that its own reporting estimated a less than one in 10,000 chance of COVID infection from touching a surface with live virus on it. In other words, some of the leading public health communication remains utterly detached from scientific evidence. Indeed, then-CDC Director Rochelle Walensky even publicly stigmatized our most effective preventive tool, stating that “the scarlet letter of this pandemic is the mask.” Imagine if she had said something like this about vaccines.

We have repeatedly exposed ourselves and our children to this virus, and most of us are not even vaccinated with the most recent formulation. The inability to cope with the idea that we are harmed by viral infections, unlike exposures to commensal bacteria, has contributed to social adoption of the tenet that getting sick will improve health through immunity. Given immunity is short-lived for COVID and many other viruses, this narrative primarily enables those who might otherwise feel helpless to deny reality rather than come to terms with widespread preventable harm, including the possibility of prevalent “silent organ damage.” This narrative has also supercharged the antivaccination movement with the idea that infection is “natural” and better than prophylaxis.

Perhaps most damning is that vulnerable people in hospitals and clinics continue to be discarded to suffer and die from nosocomial infections because decision-makers still refuse to implement the measures necessary to prevent disease, even though airborne transmission is now clearly codified. As a working bioethicist who regularly reviews adverse event reports about vulnerable patients dying of hospital-acquired COVID infections, and indeed other airborne pathogens, this is deeply unsettling.

Life will never truly be convenient or comforting while we turn a blind eye to the spread of harmful and disabling disease in our communities. Denial and inaction are not solutions. Demanding clean air just as we demand clean water is the solution. We must learn this lesson in order to stop the spread of COVID-19 and to avoid the worst outcomes of the next pandemic, which could strike any day.

And it will probably be another airborne virus.

---

Blake Murdoch is a health policy academic, bioethicist, lawyer and science communicator at the University of Alberta’s Health Law Institute. He studies online health misinformation and pandemic discourse, engages in active ethics oversight for ongoing scientific research, and assesses disconnects between scientific evidence, ethical principles and policy.

This article was originally published on Healthy Debate.