Canada's health care is bruised, but not broken

Reflections on the state of health care, with Dr. Joss Reimer

2024 brought new sets of struggles to health systems across the country. Dr. Joss Reimer, president of the Canadian Medical Association (CMA), reflected on growing challenges, and some solutions, in an end-of-year interview and explained why despite everything, she’s cautiously optimistic.

“It’s very clear that the system is still in crisis. There's a lot to be frustrated about,” she said.

Emergency rooms across the country are closing more frequently than ever, wait times for surgeries and diagnostics are at record highs, and over six million Canadians don’t have a family doctor.

Last year, the CMA engaged Canadians in cross-country consultations, through which Reimer says it found consensus on a shared priority: keeping health care accessible for everyone, regardless of their ability to pay.

Steps forward, steps back

The CMA’s consultations resulted in a series of policy recommendations to fix Canada’s health care woes. Though the document isn’t meant for casual reading, nested within it is a suggestion sure to resonate for many: provinces and territories should be prohibited from allowing out-of-pocket fees for publicly insured care.

In early 2023, then-Health Minister Jean-Yves Duclos pledged to issue an interpretation letter in response to reports of patients paying out-of-pocket to get MRI and CT scans.

The purpose of an interpretation letter would be to clarify what provinces and territories are able — and not able — to allow when it comes to patient fees for health care, in keeping with the Canada Health Act.

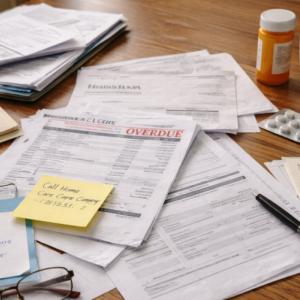

Nearly two years after Duclos promised the letter, membership fees for nurse practitioner-led clinics and the rise of for-profit virtual care have emerged as signs of a health care system that’s increasingly pay-to-play.

The current Minister of Health, Mark Holland, has been teasing the interpretation letter’s release since the summer, when a leaked memo from his office suggested it would effectively be a crackdown on patient fees for virtual care and NP clinics.

In a November interview with Canada Healthwatch, Holland said "the interpretation letter is coming soon." When asked for a specific timeline he said, "imminent is the best way I can describe it."

But now, as the federal government undergoes a turbulent shift into campaign-mode, the interpretation letter and other key reforms are at risk of being sidelined, becoming casualties of the political climate.

“We haven't seen much coming out of parliament in the last little while,” Reimer said. “It seems like decisions within the house are at a bit of a standstill.”

“That's discouraging for us. Canadians want action from government.”

Amid these challenges, Reimer said it’s worth celebrating some positive developments. Chief among them is the removal of mandatory sick notes in three provinces, a move she and the CMA have been pushing for. The change reduces paperwork for family physicians in those provinces, freeing them up to spend more time on patient care rather than administrative work.

While it may seem pedestrian, Reimer says it’s not a minor issue. "A third of Canadians have to get a sick note every year. We surveyed Canadians, and over 80 per cent of them told us they would rather go to work sick than get a sick note."

Progress on other issues had been promising last year but has slowed significantly with recent political tumult.

Reimer noted the stalled progress of Bill C-72; long-awaited legislation designed to improve digital health infrastructure across Canada. She says the bill is key to improving care coordination and addressing system inefficiencies, but has yet to move beyond its initial stages, and now seems less likely to make it into law.

The inking of new federal-provincial health agreements as well as shifts in provincial funding models mark significant steps in the right direction. British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, and Alberta are moving away from fee-for-service payment structures, aiming to better incentivize care that is more comprehensive.

“We want to make sure family physicians can provide the kind of care Canadians truly need, especially as their patient populations age,” Reimer said.

Redefining ‘primary care’

Reimer sees team-based care as the future of primary care, enabled by the shift away from fee-for-service payment models. This approach brings physicians, nurses, pharmacists and others together under the same roof, leveraging each other’s expertise to provide more comprehensive care.

“The key is that we’re doing it in teams, not creating further siloed care providers,” she said. Yet, barriers remain. Most provincial funding models make team-based care virtually impossible to implement and scale, with physicians often needing to hire and pay other providers if they want to work alongside them.

Expanding the scope of practice for health professionals, such as pharmacists, is another step toward fully realizing team-based care. Across the country, provinces in 2024 asked pharmacists, registered nurses, and nurse practitioners to do more.

In his November comments, Mark Holland said, "The solution isn't always more doctors or even more nurses. It's expanding the definition of primary care and moving everybody to top-of-scope. There are a lot of circumstances where folks don't need to see a doctor."

Reimer says she’s enthusiastic about expanding scope for pharmacists and other professionals, but that it must take place within the framework of team-based care. Otherwise, she warns, services remain siloed and risk becoming more fragmented than they already are — particularly in settings where corporate pressures on providers might not align with patients’ best interests.

Reimer acknowledges the frustration many Canadians feel about the state of health care, but her outlook remains positive. “While some of these changes are going to take time, we are moving in a direction that’s going to make the system stronger.”